Between 11 – 12 January I attended the Public Governance and Emerging Technologies: Values, Trust, and Compliance by Design Conference held in Utrecht, Netherlands.

The conference was hosted by the Chain Project, a Dutch Research Council (NWO) funded initiative that focuses on blockchain in the network society.

From the project website:

- Governments are developing blockchain applications together with companies to improve their services. This might lead to complexity and uncertainty about government responsibilities or the optimal design of rules. This interdisciplinary project investigates how distributed technology – in this case blockchain – combined with smart contracts (rule-based algorithms) can be designed in a transparent and legitimate way, so that citizens can trust the government.

The conference aimed to combine expertise from multiple disciplines such as law, sociology, philosophy, STS, public governance, and computer science, to facilitate discussions and further knowledge about emerging technologies, public values, trust, and compliance by design in public governance.

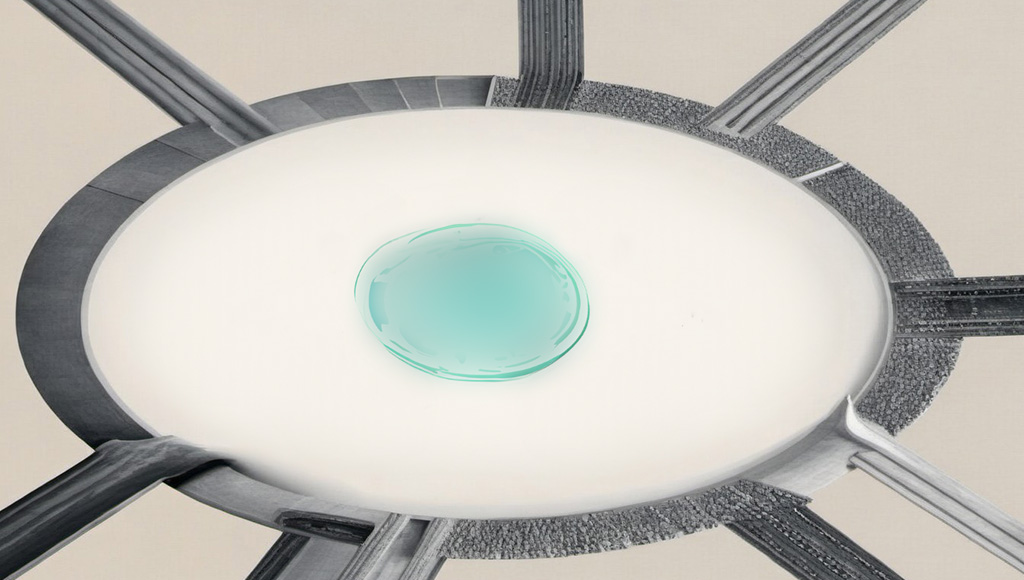

The event was held in the splendid setting of the Paushuize (Papal house) in Utrecht’s old town, a beautiful structure that was built around 1517 in a gothic influenced renaissance style by the future Pope Adrianus VI.

The conference included two Keynote addresses and three panel tracks: values, regulatory compliance and governance. The full program (which includes abstracts from the panel participants) is available to download here.

Keynote 1

The opening Keynote ‘Learning from cars and trains: (Re)gaining democratic control over digital practices’ was delivered by Prof. Barbara Prainsack from the University of Vienna.

- Amongst a host of other publications, Professor Prainsack is co-author of the Governing Health Futures 2030 White Paper on Data solidarity. This paper calls for the implementation of a solidarity-based data governance framework that would allow digital technologies in health and health care to be driven by public purpose and not by profit. A key element proposed is a stronger emphasis on collective control, responsibility and oversight. Alongside her academic work, she is Chair of the European Group on Ethics and New Technologies, an advisory board to the European Commission.

The following notes were taken during the keynote:

During an overview of recent historical events, the speaker described how Facebook had knowledge that their business practices were causing harm to its users (promoting addiction) but chose to do nothing about it. Whistleblower Frances Haugen brought this issue out into the public domain, but it has not been resolved. Prainsack sees its non-resolution as primarily a problem of lack of democracy, suggesting that democratic approaches could address some of the issues raised.

Prainsack went on to propose both a need to develop new rights and the protection of those already existing. Interesting examples suggested of new forms of rights might be the right to human contact (if we think about the robotization of elderly care for example) or the right to remain illegible so that data that pertains to an individual could not be used for AI training purposes.

She also proposed 3 layers of digital control: facilitating, prevention and taxation, before introducing the online Public Value Assessment Tool, which addresses the question of when does data use have public value?

- The Public Value Asessment Tool was co-created by a team of business and sustainability experts in 2021, and enables leaders to identify strengths and improvement actions to enhance company public value performance across four spheres of action related to the nine Public Value Principles©: Leadership & Governance, Business Model & Value Creation, Data & Technology and Impact Management.

Several of these arguments show similarities to comments made by Foundation President Piero Bassetti and relayed in the International Handbook on Responsible Innovation. In an interview with Sally Randles, Bassetti stated that ‘we are not interested if an innovation is responsible, we are interested in whether it is democratic or not. And if those democratic are responsible’. A comparison between Professor Prainsick’s approach and that of President Bassetti might seem to show a shared belief that the frame of fair market competition on its own is inadequate if the (necessary) aim is to democratize the innovation process, which thus requires some form of democracy-based intervention.

The Plenary Keynote

The Plenary Keynote was ‘Digital technologies and ‘ex ante’ protection of fundamental rights’, delivered by Prof. Janneke Gerards of Utrecht University.

- Amongst her many publications, Professor Gerards is author of the recently published General Principles of the European Convention of Human Rights, which offers insight into the concepts and principles that are key to understanding the European Convention and the Court’s case law. She is also chair of the Advisory Council of the Netherlands Human Rights Institute, chair of the Committee for Freedom of Science of the KNAW and member of the Scientific Committee of the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA).

The following notes were taken during the Plenary:

Alongside opportunities, algorithms present risks and challenges that current human rights cannot address properly. They are however black box systems, which means that we don’t know how we ourselves are affected by them. They also present the problem of many hands.

There is a need for generic ex-ante protection, through impact assessment for algorithms.

Responsible use of AI systems in public administration requires an interdisciplinary team and intersubjectivity. It is important to be able to account for choices. (see the discussion of explainable AI later in this post). The importance of process and substance needs to be understood and promoted through training for civil servants and the creation of a type of fundamental rights roadmap for algorithm developments.

The fundamental questions should be why, what, and how?

Professor Gerards explained that there is a voluntary national algorithm register in the Netherlands and a city-wide register in Amsterdam, questioning whether registration within such a register could become compulsory.

Panels

The conference hosted three panel tracks focusing on blockchain used in governance, from the taken-for-granted standpoint that the unilateral exercise of public governance is a thing of the past: Local and national governments are currently experimenting with algorithms, a movement that challenges values in a world of hyperconnectivity. The following are notes taken during the panels I followed.

Governance of cybersecurity panel.

All panelists were trained in law.

Security is a public good. It is much more than just privacy.

Computer security is part of information security, and both are prerequisites for digital life security. Security in cyberspace is an essential condition for trust.

Public Private Partnerships are important as they represent a means of extracting expertise from the private sector for the benefit of the public sector.

One major problem is that ownership remains in private hands.

Oversight is necessary to uphold rights.

Could we envisage an international charter of fundamental rights in cybersecurity?

3 questions: which new rights does technology bring and how are they related? Which rights are violated? How can we address the emergence of problems with rights that do not yet exist?

What is the best way to organize an EU model of governance?

Private actors are the gatekeepers, leading to questions about which kind of constitutionalism we might need.

Philosophy of AI panel

The idea of inductive inference runs through AI, it does not generate new knowledge but only offers prediction based on past observations. This is inherently flawed.

There is a growing call for and field developing in explainable AI. Explainability allows questions of accuracy and fairness. Public governance holds the responsibility of explaining its application of AI systems.

All EU tax administrations use AI systems. Should AI models of taxation be published and open for scrutiny?

Can fairness be automated, or is it a human trait

PublicSpaces was an example offered of a coalition whose aim is to design a new platform for social interaction, where users are not viewed as exploitable assets or data sources, but as equal partners that share a common public interest. It is committed to providing an alternative software ecosystem that serves the common interest and does not seek profit.

(Un)biased AI in public governance

There are several barriers to developing ethical AI: general, technology related and human related, as well as knowledge, support and process barriers

What is the relationship between public values and responsible algorithmitization?

There is a lot of human on-site negotiation of ethical practices during AI use.

There is a need to rethink value sensitive design: from artefacts to sociomaterial algorithmic systems and from design to continuous design.

There is also a need for transparency and non-exclusivity (a human is required so that decisions can be attributed to the administration, see the question of fairness raised above).

There should be a push to motivate the act and make the code public.

An algorithm is not neutral, we should question its degree of accuracy.

There is a risk of the incorrect functionality of administrative power and de-responsibility for civil servants (this is an argument that often comes up in Responsible Innovation debates, the implementation of systems and protocols leads to de-responsibility).

Governance by and of Technology

Ther are three typical feelings about technological development: Optimistic, technology as remedy; a sense of oppression (the machines are not fool proof); ambivalence to technological developments.

Developments affect the concept of rule of law.

Does AI comply to GDPR?

Has the state lost its power if it has to pay for data to use in its AI?

Three forces shape evaluative mechanism: international lawyers, public audience, and domestic authorities through funding and regulation (which role can and does this play?) Owners (large technology corporations) act like states in the US, but the EU has regulatory capability in Europe. How can this situation be re-shaped using anti-trust laws?

Some final Thoughts

This was a very well run, eye opening and interesting conference. The speakers came from a broad range of fields, which offered participants an array of perspectives. The setting was wonderful, as was the hospitality, and the organization of the spaces on offer led to a great deal of interaction during the coffee pauses.

The public governance and emerging technologies topic brings two of the Bassetti Foundation’s focus points under the spotlight. Regular readers may know that Foundation President Piero Bassetti is a former President of the Region of Lombardy, and that this experience of governance (amongst many others) is represented throughout the myriad of approaches and events promoted by the Foundation over the years.

One interpretation of this influence might be that the Foundation could be seen as not really interested in the governance of technology at all, but interested in the governance of a society that is in many ways shaped by technological developments that are outside of the control of those governing (and in private hands as noted above).

From this perspective, rather than requiring governance and regulation, the path of technological development should be democratized. We might see this as a missing part of the democratic model that is needed in order to better govern. This further embedding of democratic principles in the system as a whole would offer those in governance a more complete set of tools in working for the public good.

From this perspective addressing technological development requires broad thinking. For example addressing the question strictly from a rights perspective could be seen as incomplete, as rights represent only a small factor within democracy. It could lead (as I feel it sometimes did during this conference) to some taken for granted assumptions that could be questioned, around the necessity to broaden public influence in the choices made by governors to adopt such technologies without public discussion and scrutiny for example.